Introduction

In this post, an Internet of Things (IOT) Motion Sensor will be created using an ESP8266 development module. For my specific setup, I will use a virtual SmartThings device and IFTTT to trigger a SmartThings light.

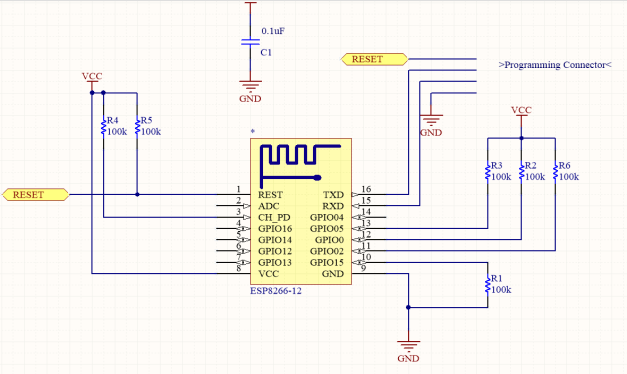

Device Setup

I created a virtual device on my SmartThings hub to decouple the detection of motion from the device being activated. That way, the device being triggered can be redefined easily and conditions can be applied to the triggering. I used this post to setup a virtual device.

Once the virtual device (motion sensor device) was setup, I created two IFTTT recipes; one to turn on the motion sensor device and one to turn it off. The IF condition is the Maker Channel’s “Receive a web request” and the THAT condition is the SmartThings “Switch On” action.

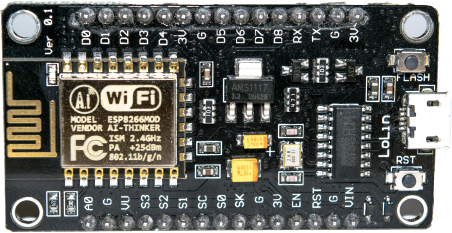

Now to flash the MicroPython binary to the ESP8266 development board. I used the NodeMCU flasher tool with the binary from http://micropython.org/download. For the most part, I just connected the board, selected the binary, and then hit upload. After a short time, the board was working. I did find this guide useful though (you can use either esptool or NodeMCU flasher, however, esptool failed for me).

Before proceeding, either download WebREPL or visit the hosted WebREPL. Once the binary is flashed and you have the WebREPL client running, the ESP hosts a WiFi network. Log into this WiFi network with micropythoN as the password. Then use the IP: “ws://192.168.4.1:8266/” with no quotes in WebREPL. This should connect and ask you to change the password and reset the device.

You’ll have to reconnect to the device’s WiFi network and reconnect in WebREPL. You now have a wireless python terminal that runs on the device.

Network Connectivity

Now, the device can be programmed without using the serial port, but only over the device’s WiFi network. To fix this, the device needs to be told on boot-up to connect to another network – allowing easier access as well as allowing the device to connect with services on the web.

The functionality to connect to a network can be added to the boot.py script. The general process for programming is to download the desired file (boot.py) using WebREPL (on the right). Then edit that program and re-upload. The starter boot.py has a few lines of code, but the following code is all you need.

import gc

import webrepl

import network

webrepl.start()

gc.collect()

gc.enable()

wlan = network.WLAN(network.STA_IF)

#Function that was on a getting started tutorial

def do_connect(ssid, password):

wlan.active(True)

if not wlan.isconnected():

print('connecting to network...')

wlan.connect(ssid, password)

while not wlan.isconnected():

pass

print('network config:', wlan.ifconfig())

do_connect('SSID', 'PASSWORD')

The device can now be connected to with its IP address. The device’s WiFi network is still hosted and can be used even while its connected to another network. One issue is that you likely don’t know the address of the device on the new network. You can still connect via the hosted WiFi network and run wlan.ifconfig() in the WebREPL shell to find the address of the device. Another way is to setup a static IP based on the MAC address of the device. Unfortunately this process varies between wireless routers, so this part will have to be homework. Another way would be to use some service like IFTTT in order to be notified of your node’s bootup or possibly create two way communication with a web server (see my previous posts for a lower level look into sending messages to IFTTT).

IFTTT integration

My previous posts explain some of the more nitty-gritty details of sending HTTP requests to IFTTT, however, these requests are greatly simplified with Micropython as sockets and web requests are handled at a much higher level. The following two functions allow the device to send messages to IFTTT:

import socket

#Simple function that handles sending a get request and printing the response

def http_get(site, port, reference, val1, val2, val3):

address = socket.getaddrinfo(site, port)[0][-1]

print('Connecting to ', site, '(', address, '):', port)

s = socket.socket()

s.connect(address)

message = 'GET ' + reference + '?value1=' + str(val1) + '&value2=' + str(val2) + '&value3=' + str(val3) + ' HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: ' + site + '\r\n\r\n'

print('Sending: ', message)

s.send(message)

print(s.recv(500))

s.close()

#Simple function to handle sending the IFTTT get request to trigger an event

def ifttt_message(event, val1, val2, val3):

http_get('maker.ifttt.com', 80, '/trigger/' + event + '/with/key/YOUR_IFTTT_KEY', val1, val2, val3)

#My bootup event that sends a notification to my phone with the LAN IP, Port, and WAN IP (currently not implemented) of the device

ifttt_message('node_bootup', wlan.ifconfig()[0], '8266', '?')

The functions are added after the other functions in the original boot.py and the last line of code is added toward the bottom of the script. This ensures that the functions have been defined before they are called (see below for full boot.py script).

Motion Sensor

The last bit of functionality that needs to be added is the PIR motion sensor. This sensor has three pins: power, signal, and ground in that order. When powered, it sends a high signal when it has detected motion and a low signal when it has not. The sensitivity and signal hold time can be adjusted using the potentiometers on the side of the device. The signal can be read by nearly any GPIO on nearly any microprocessor. The ESP8266 with Micropython is no exception.

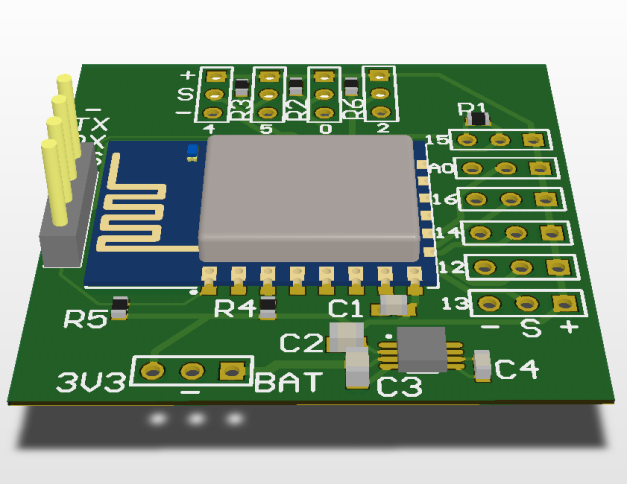

PIR Motion Sensor

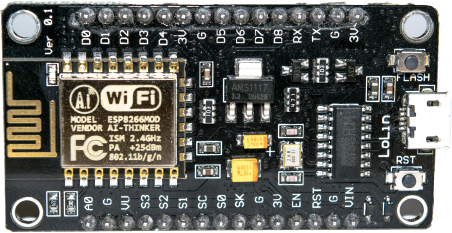

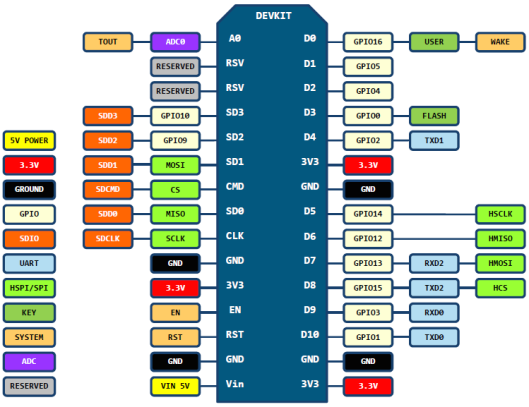

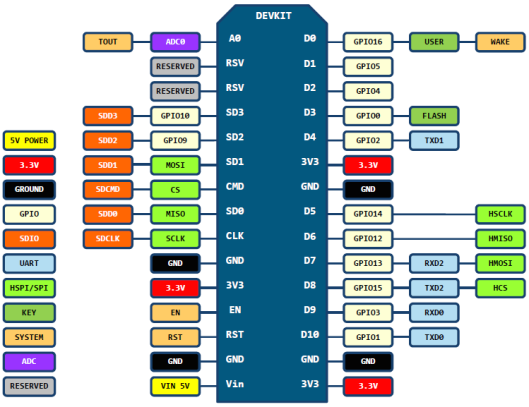

The motion sensor can be connected in the following way; VCC to 3.3V, signal to d1, and gnd to gnd. Here, pin d1 was chosen to be the digital input. Below is a good chart on the pinout of most dev kits. Here, D1 is GPIO5 or just 5 in Micropython.

All that remains is to write some code that reads the motion sensor’s signal and responds (here I’ll be sending an IFTTT message). As I plan to have multiple devices with many different applications, the more general functionality is left in boot.py while application specific code is placed in main.py. Follow the previous link to see my implementation. The code has an interrupt that responds on rising edges which handles triggering motion. A loop is used to wait for motion timeout as well as send messages. I originally designed the whole program to operate in the interrupt function, however, it seems like the socket library must not be called within an interrupt. As calling socket.send() from either a timer interrupt or pin interrupt failed with errors such as “MemoryError” or simply exiting the interrupt routine.

Conclusion

When I walk into my bedroom, my SmartThings light comes on after a second or two. A short amount of time after I leave my bedroom, the light turns off. This comes at a price tag of about $5; $3 for the ESP dev board, $1-2 for the PIR sensor, and a few jumpers. Pretty good price compared to the $30+ motion sensors found online. However, one issue is that the reaction time is much slower than I would like. Speeding up the reaction time would be a nice future project.

Here is the boot.py I use with some added functionality I found useful along the way.

Useful Links

Programming an ESP8266 Dev board

Micropython Reference (ESP8266)

Micropython binaries